THE ORIGIN OF THE NORFOLK BROADS

A CLASSIC CASE OF CONFIRMATION BIAS

BILL SAUNDERS

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards

How Joyce Lambert's concept was developed.

"It is a capital mistake to theorise before you have all your evidence. It biases the judgement."

"A Study in Scarlet." Conan Doyle

The phenomenon of Confirmation Bias was well known long before behavioural scientists got hold of it in the 1960s.

"There is little in the published history of Broadland to suggest an 'artificial' origin. Enormous quantities of peat have been removed; the flooding of the turf pits must have produced a major change in the landscape of Broadland, even if it were not an economic disaster. Yet all this activity and change have gone unrecorded in published writings on the history of the area, and forgotten by local folklore and tradition." Smith, 1960

If a sudden, major change in the landscape is not mentioned in any history books, what reason is there to think that it ever happened? Why would this disastrous flooding have started?

Proponents of Joyce Lambert's concept would presumably answer the first question like this:

the broads are great peat pits which were subsequently flooded. This subsequent flooding must have caused a major change in the landscape.

In contrast, the original answer to the second question was based on seemingly solid fact, rather than theory.

A RISE IN SEA LEVEL?

In the late thirteenth century, the level of the sea relative to the coast at Great Yarmouth was at least thirteen feet lower than it is today; it then started to rise at a rate of about three feet every century, and continued to do so for the next three hundred years. This was the conclusion of Charles Green, "one of East Anglia's most prominent and active archaeologists, with vast experience of excavations (often for the Ministry of Works) from the Roman port of Caister, near Yarmouth, to Saxon and medieval sites all over Norfolk." ("The Broads.", E.A.Ellis, Collins, 1965).

Joyce Lambert's revelation in 1952 that the Broads were man-made raised some critical questions, which in turn revealed the need for more research to provide authoritative answers. Charles Green had been co-opted onto Lambert's team in 1953 to bring his expertise to bear on two of these questions: firstly, how had pits of such size and depth been dug out without flooding? Secondly, were there enough people living in Broadland to have carried out such a major feat of civil engineering, and to have consumed such vast quantities of peat?

(Note: Another member of the team, the geomorphologist J.N. Jennings, had argued {"The origin of the Broads", R.G.S.Research Memoir No.2, 1952} that the broads could not be man-made because inter alia the task of digging such huge deep pits would have been an impossible one, and anyway the population would have been too small).

What had prevented these great pits from filling up with water while they were being dug? Joyce Lambert saw the answer as lying in a simple choice:

"The sheer size and depth of the basins point either to more favourable conditions for the deep digging of peat at some time in the past than at the present day in the East Norfolk valleys, or else to the unlikely engineering in early historical times of effective methods for preventing continual flooding while the pits were being worked." Lambert et.al., RGS, 1960, (Lambert and Jennings, Part1)

In short, either water levels were so low that the basins would have stayed dry all by themselves, or the makers of the broads had used techniques to keep them dry which, as Lambert and Jennings made clear, must have included the use of some sort of pump or bailing device.

- When it came to the question of how the broads were created, Charles Green, the archaeologist, therefore confined his researches to looking for evidence, which he confidently predicted would exist, of a period when the level of the sea relative to the coast at Great Yarmouth had been very much lower than the present day.

The brilliant geographer and historical geographer, Clifford Smith, then an assistant lecturer at Cambridge, was recruited to answer but one question: when had the broads been created? More specifically, he saw his task as being "to establish the period over which the pits were being dug, the dating of the subsequent flooding, and the conditions under which the turf-pits were finally abandoned." (Smith, 1960)

- Further research by all members of the team was thus conducted with the objective of confirming the thesis that great big pits had been dug out by hand, probably when water levels were very low, and had flooded subsequently, probably when the sea level rose.

Green began with data from seven existing archaeological sites, which had been excavated, either by himself or others, in the vicinity of Yarmouth. The "results . . . proved difficult to interpret in the light of the views implicit in current literature on the history of the estuary" (Lambert et al., 1960, Green and Hutchinson, Part III), although none were inconsistent with a lower sea level. However, he later had the opportunity to examine "vast excavations involved in the construction of a new electricity generating station on the South Denes at Great Yarmouth, which began in 1954 and ended in 1957." (ibid.).

(Note: Through the good offices of the Assistant Resident Engineer of the Consulting Engineers to the Central Electricity Generating Board, J.N.Hutchinson, B.Sc., A.M.I.C.E., Green was admitted to the site as an official observer, which enabled him to carry out the general archaeological analysis. Hutchinson helped Green by keeping records and organising the salvage of archaeological material; he was named as co-author of Part III of the 1960 book).

There was already evidence that the land had started to rise out of the sea soon after the start of the first millennium AD, and Green found compelling clues in the South Denes site, which, taking all the data from the seven other sites into account, prompted him to comment as early as 1956:

"The main difficulty [with the theory of a man-made origin] lay in understanding how many great peat-cuttings to a depth of 10-12ft. or more could have been made in the face of water infiltration. The new Yarmouth evidence goes far to resolve the difficulty. For if the the whole area stood at least 10ft. higher above sea-level, the reduced high-water area in the lower estuary would have led to a fall in the upper-valley fresh-water table. The possibility of cutting peat and the subsequent flooding of the hollows as the medieval trangression progressed are explicable and even easy to understand." The Times, May 14th, 1956

Green's final verdict, in his contribution to the 1960 book, raised the land even higher:

"Although the evidential value of these records is clearly variable, the sum of the inference leads to one conclusion only. The coastal region, as specifically dated by the South Denes pottery and the South Quay finds, and allowing for a slightly greater tidal range than that of today, still stood some 13.0 ft (4.1m) higher above the sea towards the end of the thirteenth century than it does today."

Charles Green had found the sort of evidence which he expected to find, evidence which confirmed his solution to the problem of continual flooding in Lambert's "great peat-cuttings"; he felt that it was sufficient to complete the task for which he had been recruited.

"Many problems relating to these changes of land and sea levels and their chronology await solution. But significant evidence of the emergence of the land in Saxo-Norman times has been adduced, an emergence which, at the time of a considerable accession to the population of Broadland, made deep peat-digging possible."

Green and Hutchinson, 1960

As he had predicted, water levels must have been low enough to allow these great pits to stay dry while they were being dug, and the subsequent flooding must have occurred under the following circumstances:

"And then the slow submergence began. At first this must have been slight, for at the time of the great flood of A.D.1287, a closely dated level in the South Denes has shown that, at that date, the land surface still stood some thirteen feet higher in relation to the sea than it does today. For a time the submergence-rate accelerated . . . . .. By the seventeenth century the land stood relatively no more than three or four feet higher than today, and the submergence-rate was decreasing . . ." Jennings and Green, "The Broads", ed. E.A.Ellis, 1965

So significant was Green's work considered to be that a sample of broken pottery and sea-shells from the South Denes site was displayed in an illuminated cabinet for the admiration of visitors to the Castle Museum in Norwich.

- For many years it was accepted as fact that the Norfolk Broads became flooded when the sea level rose.

- Many reference sources still make this assertion, seemingly in ignorance of later research.

One problem, however, was immediately apparent.

"Thus, while the stratification of the Upper Peat does not exclude a period of drier conditions and may in fact suggest it, there is no evidence of a contemporary fall in the water table comparable in magnitude with the medieval land-sea level changes suggested by the archaeological evidence from the Yarmouth Spit (Part III)[my italics]. Indeed, on present scanty information, it seems more likely that any such changes operated more in relation to changes in gradient in the rivers themselves between the inner parts of the valleys and the Yarmouth outfall than in any major lowering of the fenland water table." Lambert and Jennings, 1960

The sea level may have been thirteen feet lower, but the fresh-water table in the upper-valley peat fens most certainly was not, nor was it low enough to have allowed the 'great peat pits' to have been dug out without becoming flooded.

- Lambert, Jennings and Smith were compelled to conclude that the solution must, after all, lie in "unlikely engineering".

All of which may serve to explain why, in the 1960 book, it was left to a botanist, a geomorphologist, and an historical geographer to speculate about possible engineering solutions to the problem of continual flooding, while the archaeologist, who was originally recruited to research such matters, and who was assisted by an experienced and highly qualified civil engineer, did not associate himself with their thoughts.

"[Water entering the workings] could probably have been dealt with comparatively easily, such as by catch-drains along the edge of the alluvium as at present and by primitive baling methods. For instance, the simple method of ladle-and-gantry, still in use in certain of the peat workings of the Somerset Levels, appears to keep diggings of fairly large size sufficiently well drained to work if maintained regularly in operation." Lambert and Jennings, 1960

"Moreover, there are numerous instances suggesting a sectional excavation of the peat with baulks left standing across the whole width of the basin, possibly to delay flooding from one section to another." ibid.

"Turf digging then, as now, was probably a seasonal operation for the summer, probably preceded by some attempt to drain off or bale out the previous winter's seepage and some upland drainage." Smith, 1960

They also revealed conclusive evidence that water will only seep through the saturated peat in the walls surrounding a deep pit at an exceptionally slow rate.

They seem not to have realised that the notion of one section of a basin flooding before another conflicts directly with their own pivotal concept of the 'subsequent flooding' of the whole basin.

- There can be no 'dating of the subsequent flooding', if the 'great' pits each became flooded a section at a time.

It was of no relevance, apparently, that the "fairly large", nineteenth century peat diggings on the Somerset Levels, where the ladle-and-gantry originated, are all shallower than any of the broads, and smaller than most of them.

Abandoned peat diggings at Cold Harbour, Somerset.

They speculated at some length, but to no conclusion.

"Throughout the foregoing discussion it has become increasingly evident that, if the theory of artificial origin of the broads is sustained, a further elucidation of the activities involved in their formation . . . . must rest with the historical worker." ibid.

"Several problems remain, however, . . .. Finally, how did the turf pits remain sufficiently dry to be workable over a sustained period before the end of the thirteenth century?" Smith, 1960

"At the present state of our knowledge, the question of ways and means must remain a matter for speculation." Lambert, Jennings and Smith, "The Broads", ed. E.A.Ellis, Collins, 1965

The opinion held by the three authors about their own speculation was clearly that more research was needed in this area by competent 'historical workers'.

- Instead, and without further research, this speculation has become accepted as fact.

The archaeologist, Charles Green had rejected an 'engineering' solution as "inconceivable" (George, 1992), had settled on the alternative solution, and (perhaps unmindful of Holmes' dicta) had sought and found the evidence to prove it.

The geographer, Clifford Smith, having failed to discover any clues in ancient maps as to when the broads were dug or when they became flooded, found them instead in fragmentary historical records. Although he warned that the evidence was largely circumstantial and the samples so small as to warrant only tentative conclusions, he felt able to state:

"Nevertheless, the evidence fits together to confirm strongly the thesis that the basins of the broads were literally dug out by hand, but that some of them at least were becoming flooded and increasingly worthless as turbaries and more valuable as fisheries from approximately 1300-1350." Smith, 1960

In his preface to the 1960 book, Professor Sir Harry Godwin F.R.S. wrote, without any discernible trace of irony:

". . ., and I greatly value the opportunity to congratulate the authors on the intregated presentation of their results, . . .".

Publication in 1960 prompted a period of public debate, from which, despite the obvious anomalies, a consensus emerged which has evolved into the established account of the origins of the Norfolk Broads:

The broads are great pits dug for peat which were subsequently flooded.

The historical evidence proves that this subsequent flooding occurred in the fourteenth century.

The subsequent flooding was caused by a general rise in inland water levels, principally initiated by a rise in sea level.

The great pits were abandoned one by one when the depth of the flooding made further peat extraction impossible or uneconomic.

Nobody really knows how the great pits remained sufficiently dry to be workable over a sustained period before the end of the thirteenth century, but some sort of bailing device was probably used.

Perhaps because of this consensus, no 'historical workers' have taken it upon themselves to throw any further light on the methods employed; the broads are great peat pits which were subsequently flooded in the fourteeenth century, so they must have been kept dry before then. How it was done, it seems, continues to remain a question which merits no more than mere speculation.

". . . the medieval excavations could probably have been kept dry by regular baling, given sufficient incentive and enough labour."

Williamson, 1997

When, in 1952, Joyce Lambert first formed the concept of great pits which had flooded subsequently, she was theorising ahead of some significant facts.

- It was not until late 1953 that Lambert became acquainted with the impermeable qualities of peat.

- Smith was yet to reveal that, as well as being dug or 'cut', turves were shaped from peat dredged up in bulk from under water.

- Smith was yet to conclude that peat digging was a seasonal activity, confined to a few weeks each summer.

OR A CHANGE IN THE CLIMATE?

It took rather longer for a second problem to become apparent. Although the evidence from the power station site was substantial and compelling, it stood alone; the rest of Green's evidence was inconclusive.

In his magnum opus "The Land Use, Ecology and Conservation of Broadland" (Packard, 1992), Dr.Martin George revealed the results of other general research into sea and inland water levels which had taken place during and after Charles Green's own studies.

"If this [Green's] claim is correct that would imply that the relative sea level has risen during the past 700 years at a mean rate 0f 0.57 cm per year. This is over three and a half times the normally accepted figure, and must therefore be viewed with great circumspection." George, 1992

All this later research had demonstrated conclusively that the East Anglian coast has been sinking into the sea for the past seven hundred years or so at a fairly constant rate of 1.6 millimetres per year, only about six inches in every one hundred years.

"Indeed, the relative levels of the clay laid down during the Second Transgression and the peat formed subsequently, suggest that since that event the fen surface has never been more than a metre or so lower than it is now. In other words, the relationship between the mean water-table in the rivers and the level of the adjoining fens has varied little over the centuries, the rate of peat accrual keeping pace with the gradual rise in sea, and, therefore, river level which has occurred since the late thirteenth century." ibid.

Beyond any reasonable doubt, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when the basins of the broads were being excavated, the level of the sea, river levels, and the water table in the fens were all around three and a half feet lower than they are now, but the surface of the fen was also lower. When the pits were first dug they were not as deep as they are today, but the mean water table was no further below the surface; conditions for the deep digging of peat would not have been much more favourable, as Lambert, Jennings and Smith had always known; without preventative measures the pits would have flooded before the fourteenth century.

The confusion created by the discrepancy between Green and Lambert on the subject of water levels was resolved. Lambert was very close to the mark, but there has to be some other explanation for the evidence discovered by Charles Green (see under "Marietta Pallis").

There had been a simple choice between two options for keeping the great pits free of water while they were being dug. Later research had proved both alternatives to be highly suspect.

Conditions for the deep digging of peat were not sufficiently favourable for the pits to have stayed dry by themselves.

The archaeological consultant had rated an engineering solution as impossible with great pits the size and depth of the broads.

There was no evidence of the existence of any form of bailing device or pump in medieval Broadland, nor of bailing as an activity.

Nonetheless, Lambert's basic proposition of "great peat pits which were subsequently flooded", from which this choice derives, seems to have remained beyond question.

Since water levels clearly were not low enough, then there had to be an engineering solution to the problem of continual flooding in large pits which were being regularly expanded, and an answer, the one tentatively proposed by a botanist and a geomorphologist, was already at hand, subject perhaps to some minor modification. A new question arose, however:

- if the great, formerly dry pits would always have been liable to flooding, and there was no significant rise in sea level, what had caused this engineering solution to fail in the fourteenth century?

As C.T.Smith had already noted, the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century was a time of "great storminess and flooding". The climate changed from the Medieval Warm Period, and by about 1340 had become relatively cooler and wetter; the change was heralded by a period of extreme weather conditions in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, before the climate stabilised. Here must lie the answer.

"Although measures were doubtless taken to prevent the peat pits from becoming flooded, periodic catastrophes, such as the great surge of 1287 would have profoundly affected the industry. In a review of the incidence of severe sea floods on the East Coast during the past two millennia, Lamb (1981) has concluded that there was a maximum occurrence of them in or about the thirteenth century, and that this coincided with the end of a run of several centuries, when the climate was of above average warmth. . . . . . .

The risk of the pits becoming permanently flooded was probably increased, not only by periodic surges, but by a rise in the height of the water-table in the valleys, caused by greater fluvial flows as weather conditions deteriorated. Lamb (1965) notes that there was a particularly high frequency of wet autumns between about 1300 and 1320. In addition, the relative sea level may, as Lambert and her co-workers have suggested, have started to rise from about 1200 onwards, as a consequence of continuing eustasis, and renewed isostasis. Finally, Lamb has pointed to the fact that tide-generating forces combined to give maximum tidal ranges in 3500 BC, 1900 BC, 250 BC and 1433 AD , and it seems likely that the higher-than-average water levels which occurred in the latter year would have flooded any pits which were still being worked 'dry' at this time" George, 1992

In listing all the evidence he could find of factors which either temporarily or permanently would have contributed to wetter conditions, Martin George makes no attempt to quantify their net effect, and omits any contrary or balancing evidence; the great pits flooded in the fourteenth century, so wetter conditions must have been the cause.

There are records of twelve sea floods affecting the then highly vulnerable area of Marshland in West Norfolk between AD 1250 and 1350 ("The Norfolk Landscape", Dymond, Alistair Press, 1985), but the only surviving record of a sea-surge in Broadland in this period is the one associated with the great storm of 1287.

The first decade of the fourteenth century has been more noted for its "mini ice-age" ("A Social History of England", Briggs, Viking, 1984).

The severest effects of the wet autumns on the Broadland harvests were confined to 1314-16 and 1318, although grain prices were also well above average in 1295, 1300, 1312 and 1323 ("Medieval Flegg", Cornford, Larks Press, 2002).

The bulk of peat production would have taken place in the summer, before the harvest, which traditionally started in Broadland on August 1st (ibid.).

1320 saw a bumper harvest, and by 1327 grain prices in Broadland had stabilised at thirteenth century levels, remaining there in almost every year until well into the fifteenth century, clear evidence that most harvests were not affected by adverse weather conditions once the process of climate change was coming to an end. (ibid.)

Peat price levels throughout the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries generally conform closely to grain price levels (see under "The historical evidence in detail - the price of peat").

There were severe droughts in Broadland in 1325 and 1335. (ibid.)

The 1341 nonarum inquisitiones for Suffolk refer to land lost due to coastal erosion, but there is no reference to fens, marshes, meadows or turbaries losing value because of flooding.

Martin George himself makes it clear (1992, Chs. 3, 11) that the outfall of the River Yare in the fifteenth century was further south than its present location and prone to silting, and that, for this and other reasons, the tidal range in the rivers inland was greatly restricted.

Neverthless, if the broads originated as great pits which were subsequently flooded, it can only have been one or more of the factors listed by Martin George that had overwhelmed "the measures which were doubtless [sic] taken to prevent the peat pits from becoming permanently flooded".

What were these measures? Martin George was the first person to have addressed this question seriously since Joyce Lambert and her colleagues in the 1950's. He also introduced an element into the speculation which up to that point had, perhaps, been somewhat lacking: common sense.

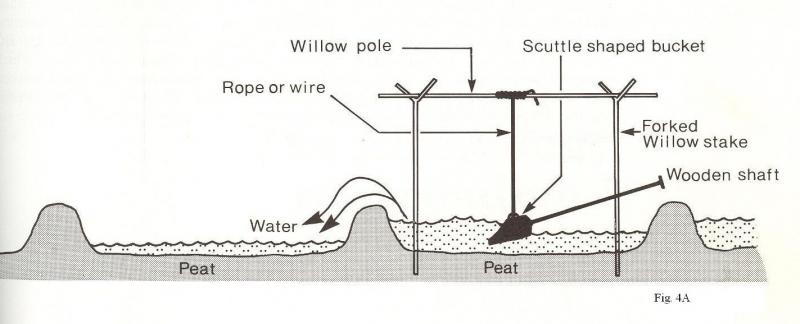

"With hindsight, it seems likely that Lambert and her colleagues laid too much stress on the difficulties involved in keeping the medieval pits free of water [*]. This would have found its way into them as a result of lateral seepage, rainfall, and extra large floods, but some sort of baling technique would have probably proved effective, provided the diggings were fairly small, and kept isolated from their neighbours by baulks [my italics]. Until about fifty years ago, most peat workings in the Somerset Levels were de-watered by 'ladle and gantry' (See Fig. 4A), and although there is no evidence that this device was ever used in Broadland, it would be surprising if one was not developed to meet local needs. . . . . . there seems no reason why [peat] could not have been dug to a depth of 3 m or more, even if the water-table was quite near the surface. "

* (Note: Lambert and two of her colleagues (but not Green) in fact grossly underestimated the difficulties involved, because what they they had in mind were great pits "the sheer size and depth" of the broads, and not Martin George's fairly small, isolated diggings.)

"The 'ladle and gantry' method of removing water from a flooded peat pit, as formerly employed in the Somerset Levels. Anecdotal reports indicate that in the hands of an experienced operator, the bucket could be swung to and fro about twenty times a minute, thus removing about 2400 gallons of water an hour. As the water level in the pit fell, the rope suspending the bucket could be lengthened."

"The baulks of uncut alluvium which separate the by-passed sites from the adjoining river (e.g. Wroxham and Salhouse Broads) would have been deliberately left to prevent water seeping from the latter into the peat pits. Nevertheless, the primitive technology would have made it extremely difficult to de-water excavations more than a few hundred square metres in extent [my italics], and it is believed that many of the ridges formerly visible in the larger broads represent baulks of peat which were intentionally left uncut in order to subdivide the basin into a series of compartments. This would have made it much easier to keep those workings which were in active use pumped out. the remainder being allowed to flood temporarily." ibid.

Even if the makers of the broads did possess an effective form of bailing device capable of raising water out of pits up to fourteen feet deep (c.f. the illustration above, and see under "How did they really do it?"), the size of the peat pits would of necessity have been fairly small. The primitive nature of the equipment, the cost of providing it in sufficient numbers, and the availability and cost of sufficient manpower to operate it, would obviously have severely limited the area to which a deep pit could have been expanded.

It was and is fatuous to suppose that more and more bailing devices, and more and more men to operate them, could or would have been deployed to keep whole basins dry as they became bigger and bigger over the centuries. Charles Green was right, and so was Martin George. This sort of 'engineering' solution is impossible with great big pits. Over thirty years after Joyce Lambert's book was published, Martin George, not an 'historical worker', but a distinguished entomologist, ecologist and conservationist, came up with a solution which began to make some sort of sense:

- much smaller pits.

Martin George realised that the broads could not, after all, have originated as 'great' pits dug for peat which were subsequently flooded.

Instead, he seems to have concluded that they originated as fairly small, adjacent pits, each of which, before the fourteenth century, was allowed to flood temporarily before being bailed out so that more peat could be dug from it; subsequently, when conditions had deteriorated in the fourteenth century due to the factors listed, all these 'fairly small' pits had flooded permanently.

But what happens to one of these 'fairly small' pits, once all the peat has been dug out of it in the twelfth, thirteenth or any other century?

There is a practical limit to the depth to which a pit can be dug, usually ten to twelve feet below the present level of the fen surface (see under "How did they really do it?").

There is a fairly small practical limit to the area.

Every time you extract peat you inevitably extend the area of the pit.

If you keep bailing it out and digging up more peat, the pit will reach that limit within a few years.

Having reached the limit, the pit is too big to bail out, so you abandon it, and start another one.

The abandoned pit becomes permanently flooded.

- By the late thirteenth century, most of these fairly small diggings in all of the turbaries would already have been permanently flooded,

The notion of an ever increasing number of separate pits, none of which is ever allowed to exceed a fairly small size limit over the lengthy period before the fourteenth century, makes no practical or logical sense; it serves only one purpose: to sustain the theory of "subsequent" flooding.

The whole point of the fairly small, separate pits is to dig up one section of a turbary after another. The concept of separate pits, each one small enough to be kept dry while it is excavated, and the concept of great big pits which are kept dry while they are excavated only to flood subsequently, are in fact mutually incompatible.

We are thus driven into this position:

either the broads originated as great big pits which were completely dug out by hand only to flood subsequently in the fourteenth century - despite the fact that it would have been impossible to keep them dry before then;

or the broads originated as numerous separate compartments, each of which flooded permanently in whatever year it was completed - despite the fact that the historical evidence proves that that the pits only flooded in the fourteenth century.

In a noble attempt to square this circle, Martin George unwittingly all but arrived at a very different, more obvious, more logical conclusion: the broads originated as fairly small, adjacent peat pits, each of which became permanently flooded as soon as all the peat had been extracted from it - pits which must therefore at some stage have been joined together to create larger areas of open water - a method identical in principle to that witnessed by Joyce Lambert in 1953.

Clifford Smith, following Lambert's concept, interpreted the historical evidence as demonstrating that "the basins of broads were literally dug out by hand", while remaining or being kept entirely free of water, and that it was not until around 1300 that any of these basins (with the possible exception of the Thurne valley) had started to flood. Fairly small, isolated diggings make practical sense, but mean that all the turbaries would always have contained ever-expanding flooded areas, which, from Smith's perspective, could not have existed.

- The original concept of the broads being the "sites of great peat pits which were subsequently flooded" was actually exploded by Martin George in 1992, but nobody noticed, not even the author himself.

SOME CONCLUSIONS

- The archaeologist, Charles Green, working in tandem with a highly qualified civil engineer, was right to conclude that Joyce Lambert's concept of great peat pits which were subsequently flooded was only viable if water levels were low enough to eliminate continual flooding as a problem.

- Along with all those who attached such significance to his findings about the level of the sea, Green was unwise to rely on what amounted to a single item of uncorroborated evidence as proof of his thesis in support of Lambert.

- Given medieval water levels as now observed and the premise of large, expanding basins, there can be no 'engineering' solution to the problem of continual flooding, and no amount of amateur speculation can alter that fact to suit Lambert's theory.

- Peat must have been dug with turf-spades, not from great pits, nor even from large sections of a bigger basin, but from quite small, adjacent pits, each of which inevitably became permanently flooded as soon as it was completed in the eleventh, twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth or any other century.

- These relatively small, flooded pits must at some stage and for some reason have been joined together to create the large areas of open water that we see today.

- Any long-term rise in water levels has resulted in a corresponding rise in the level of water in peat diggings which were already flooded.

- No "major change in the landscape" was recorded in historical writings, nor can "local history and folklore" be accused of having forgotten it, because there was no 'subsequent' flooding' in the fourteenth or any other century.

- Smith's ingenious fitting together of the small samples of circumstantial evidence contained in the medieval documents must also "therefore be viewed with great circumspection".

Copyright 2009 The Medieval Making of the Norfolk Broads. All rights reserved.

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards