THE ORIGIN OF THE NORFOLK BROADS

A CLASSIC CASE OF CONFIRMATION BIAS

BILL SAUNDERS

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards

The making of Ormesby Broad

"Conclusions drawn from such small samples must necessarily be tentative." C.T.Smith, 1960

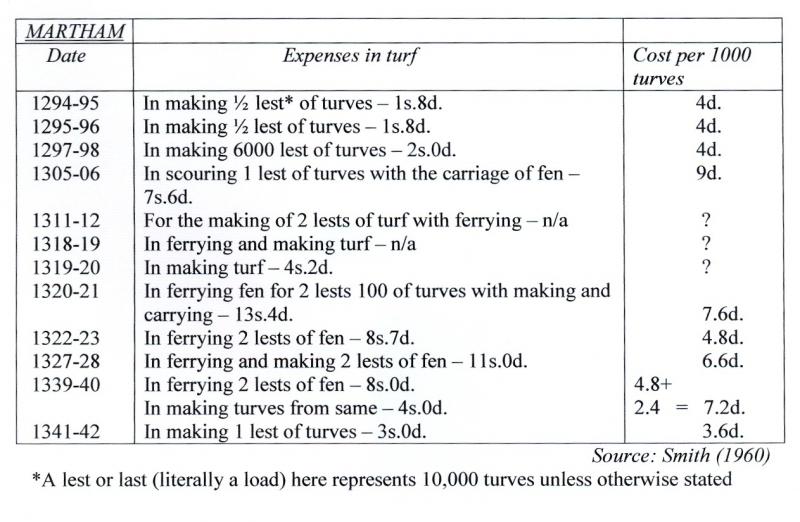

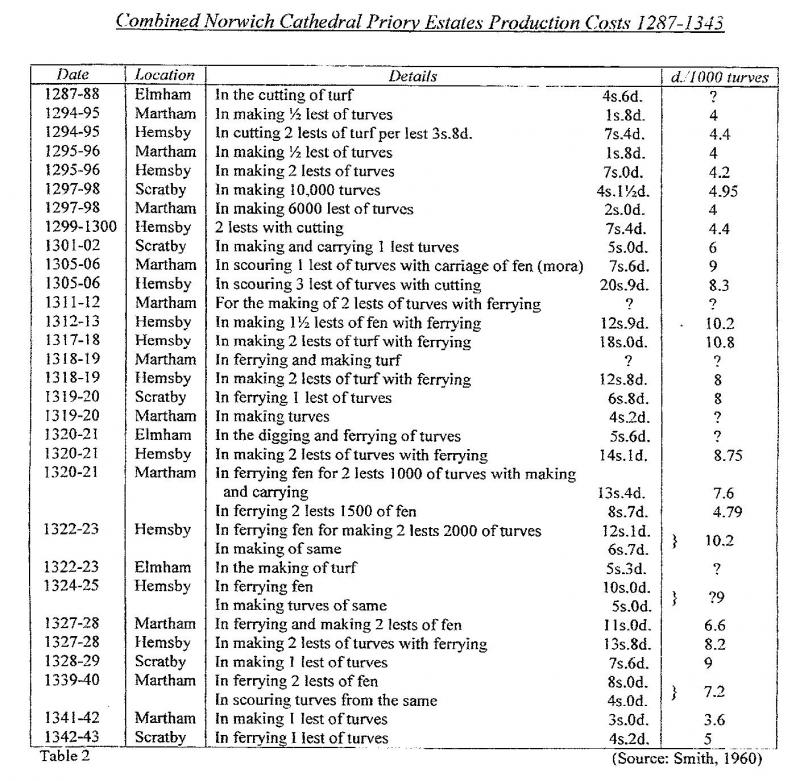

Here is the central body of evidence from which Smith concluded that a great, dry pit, which was to become Ormesby Broad, began to fill with water early in the fourteenth century, and that it was later abandoned in the 1340's, because, by then, the depth of the flooding had made any form of peat extraction impossible.

The manor of Martham Hall formed part of the extensive estates of the Norwich Cathedral Priory. Set out above are all the details which have survived of the costs of peat production from the manor's South Fen turbary, situated in that northernmost part of Ormesby Broad which lies in the parish of Martham.

Martham, South Fen Hemsby and Scratby

Although turves were also produced for sale, all the cost figures are for 'subsistence ' turves, for use in the manor's own hearths and ovens. After 1341-2, 1000 turves were purchased in 1349-50, and the records only resume in 1359-60; small quantities were then either purchased, or produced at Martham, later from the manor's other demesne turbary at Medeswykes (or Medeswyck).

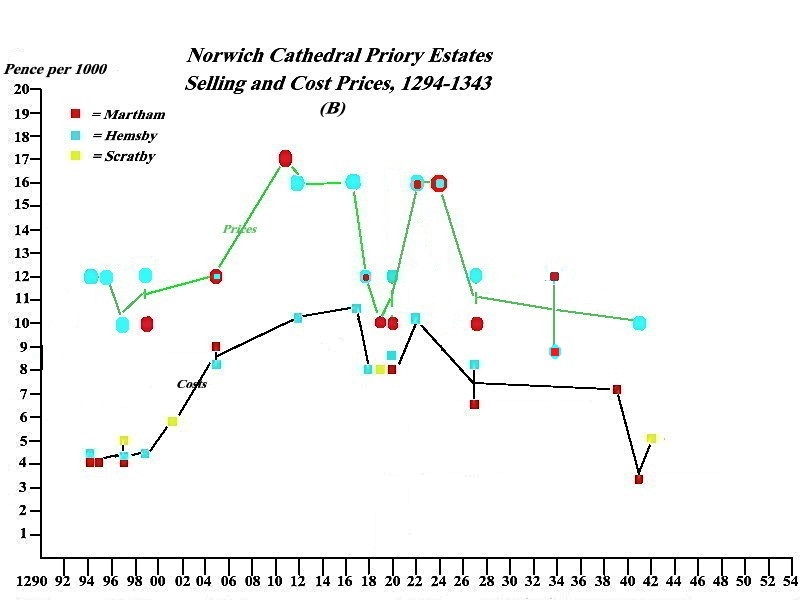

Smith sees in the above "striking evidence of a series of changes in this [14th] century", for which he finds corroboration in similar cost records from two other manors held by the Priory, Hemsby and Scratby, both with turbaries in a different part of the Ormesby basin.

" . . . . it is clear that turf production at Martham falls into three clearly distinct periods. In the first period, up to and including the year 1297-8, no turf seems to have been sold, but what turf was made cost only 4d. per 1000 to make." Smith, 1960

"Up to 1300 or thereabouts, turf was cut, presumably from a working face into the shapes required for fuel . . . . ." ibid.

"From 1305-6 to 1339-40 the characteristics of turf production and sale were quite different. Substantial manorial revenues were drawn from the sale of both tithe turves and manorial turves. The total cost of making turves shows a sharp increase to 9d./1000 in 1305-6, more than double the costs recorded in earlier years. Costs declined in subsequent years but never fell to the levels of the thirteenth century." ibid.

"Between approximately 1305 and 1342 then, it seems likely that the turbaries at Martham and Hemsby had become partially flooded, thus preventing dry working, but permitting either dredging from the sides of a boat, or the cutting of turf from the sides of a turf pit from a boat." ibid.

"What is clear, particularly from the entries for 1320-21 and 1339-40, is that at least two sets of operations were involved. First came the "the ferrying" of fen (mora) which is separately costed at 4s. per last in 1339-40. Secondly came the making or scouring of turves from the fen." ibid.

"It is this division into two processes which appears to be responsible for the much greater cost of producing turves after 1305". ibid.

"In the third period, from 1341, no further sales of manorial or tithe turves were made, and very little is produced even for subsistence." ibid.

"It may well have been new floods which put an end to the large-scale extraction of turf at Martham in the 1340's. The turf pits there were deep, and once they had become completely flooded the dredging of turf would become impossible and little turf remained between the old cuttings and the upland margin." ibid.

It is thus from the interpretation of a tiny sample of records, specifically these Martham records, but supported by what Smith describes as 'comparable' evidence (see below) from the Priory's estates at Hemsby and Scratby, that he arrived at this thesis of how Ormesby Broad was created.

- The established account of how all the broads were created derives from this by analogy, with little additional evidence.

Three stages in the creation of a broad are perceived:

- Stage One A pit is excavated and extended within the turbary simply by the cutting of turves with turf-spades from working faces. During this stage, the entire basin thus created, whatever its size and depth, remains or is kept free of water.

- Stage Two The whole basin becomes 'partially' flooded'. This means that standing water completely covers the floor of the basin, but not to any great depth. The conventional use of turf-spades is rendered impossible, but the water is sufficiently shallow to allow peat to be dredged up in bulk from the bottom and deposited into boats. Actual turves are produced either by shaping this bulk peat, or by using boats to cut them from the sides of the basin. The introduction of these more elaborate and therefore time-consuming methods causes the cost of turf production to escalate.

- Stage Three The basin becomes 'completely' flooded. This means that the water has become too deep to permit dredging. The turbary is abandoned.

This fairly elaborate structure rests on a small evidential base. How secure is it?

There are two immediate problems, the first being the 1341-2 entry: "in making 1 lest of turves" at a cost of 3.6d. per 1000. The wording is identical to entries in the 1290's, and the cost actually lower, yet Smith asserts that during his notional second period "the characteristics of turf production and sale were quite different", and also that "costs never fell to the levels of the 13th century".

This is only one item in an already tiny sample, but if you include the data from Hemsby and Scratby, the actual facts point to only one conclusion: costs in the first half of the 14th century rose, fluctuated and then did fall back to 13th century levels.

See below for this data in tabular form. Source: Smith, 1960

This, of course, is not consistent with the concept of a great pit becoming progressively flooded before being finally abandoned for that reason. Wittingly or unwittingly, Smith evades this entry by juggling with the dates of his notional periods. Logically the second period should be "between approximately 1305 and 1342" as he states at one point (p.98), that is to say ending when the records fall silent, rather than "between 1305-6 and 1339-40", as he states elsewhere (p.94). The confusion is compounded by "In the third period, from 1341, . . ."

The second immediate problem stems not from a single entry which Smith appears to evade, but rather from a small body of evidence which must have evaded him.

"As at Scratby, the Priory held a small estate in Ormesby for which the bailiff's accounts survive for only four consecutive years. Their greatest interest lies in the information given in the 1337-38 account about the peat production which must have come from the turbaries in what is now Ormesby Broad. In Norfolk peat was dug in long blocks called turves, about three and a half inches square and two to three feet in length. Ten thousand such turves made a last. In 1336-7 ten and a half lasts were produced at Ormesby, that is 105,000 turves, enough peat to fill a barn. The turves, cut from the water-logged ground in summer and stacked to dry out on the marsh, had to be removed before winter. In 1338 two lasts were used on the manor, five were sold and the rest were sent to the Priory by water. Eight men were employed for two days at a cost of 12d. to take forty six thousand thousand turves by horse and cart to Yarmouth where they were stacked on the quay to await the priory boat. A heap of fuel the size of a small barn must have been a temptation for thieves, so a man was hired for 6d., that is two or three days pay, to watch over the peat until it was taken safely to Norwich. Evidence from the Priory accounts suggests that the number of turves was not exceptionally large that year."

"Medieval Flegg", Barbara Cornford. Larks Press. 2002

Just as Smith provides clear evidence of the presence of water and boats in the Ormesby basin in the first half of the fourteenth century and of different production methods, Cornford provides clear evidence of turves being cut in large quantities in that same basin towards the end of that same period.

- The presence of water did not prevent "dry working"; other methods were being used as well as cutting, not instead of it.

There are other difficulties with Smith's thesis ranging from the obvious, but not necessarily insuperable, to the less obvious, but probably fatal.

The first period

"Up to 1300 or thereabouts, turf was cut, presumably from a working face . . . ."

The end of this notional first period is stated, but when is it supposed to have begun? Where is the evidence that other methods of turf production were not also employed during this period? Where is the evidence that water was not present in sections of the turbary which had already been excavated?

Smith reckoned that an average household would have consumed about 8,000-10,000 turves a year. We are invited to share the conclusion that the "making" of a total of 16,000 turves over three years between 1294 and 1298, at a constant cost of 4d. per 1000, constitutes proof that the entire basin of Ormesby Broad had been dug out as a single great pit, all of which, up till that time, had remained free of water ever since its excavation began.

The second period

" . . the turbaries at Martham and Hemsby had become partially flooded thus preventing dry working."

Turves were cut to create the basin of Ormesby Broad down to a depth of fifteen feet*. Smith's notion of 'partial' flooding, which allowed dredging from the bottom, would have meant standing water no more than four feet deep covering the entire excavated floor of a turbary (see under "'Dydays', etc."). What would have prevented the conventional cutting of turves down to a depth of eleven feet instead of fifteen?

"The cutting of turves from the sides of a turf pit from boats" hardly seems viable in this context; it would have meant undercutting a ten foot overhang.

Conventional wisdom (see also under "Dydays, etc,") has it that the purpose of dredging peat from the bottom was to maintain supplies of the high quality brushwood peat. According to Smith, 'partial' flooding would have made brushwood peat inaccessible to turf-spades. In a pit of this depth, that is patently a misconception.

*(Note: Smith may have assumed a more standard depth of only ten feet. Stratigraphical research by Lambert and Jennings did not include Ormesby Broad (see under "The physical evidence").

" . . . the characteristics of turf production . . . were quite different."

The complete sample of the surviving data about the cost of producing subsistence turf between 1287-8 and 1342-3 at all the Priory's manors is contained in an appendix at the end of this section.

These records contain the earliest clear evidence of the presence of water in a peat pit; they contain the earliest clear evidence of different methods being used to produce turves, and they contain clear evidence of two distinct modes of on-site transport being used in a turbary; but, again, with the absence of earlier comparable records, why is this "striking evidence of change"?

- The existence of a different, two-stage method of producing turves is clear from seven entries, five from the Martham records, two from Hemsby. At Martham in 1305-6, the 'fen' or bulk peat is carried, not ferried.

- There are twenty entries in the combined records between 1305 and 1343 which contain no reference to two stages; turves are simply 'made'.

- There are sixteen references to ferrying; in ten of them the cargo is explicitly turves, fen in only six.

The proportions in the tiny sample of data taken only from Martham are significantly different.

Smith claims that two Martham entries "particularly" make it clear that new methods have completely replaced conventional turf cutting in these turbaries, but, apart from all the above, there is another inconvenient item of evidence.

"Elmham [manor] also belonged to Norwich Cathedral Priory, and produced some turf, but lies well outside the Broads area in the Upper Wensum valley. Sample figures over the same period give the following results:

1263-4 Turves bought 3s. 4d.

In expenses in turf 4s. 5d.

1287-8 In the cutting of turf 4s. 6d.

1319-20 In the purchase of turves 2s 10d.

1320-21 In digging and ferrying turves 5s. 6d.

1322-3 In the making of turf 5s. 3d.

Smith, 1960

In 1320-1, the Priory's manor at Elmham recorded the expenditure of 5s. 6d. in "digging and ferrying" an unspecified number of turves.

Elmham is indeed in the Upper Wensum valley, but where were these turves produced, and others purchased? Not at Martham, but surely not locally either. It was gravel which was dug from the flooded pits in the water meadows of the river Wensum near Elmham, not peat. Turves were presumably readily available for purchase in Norwich, and the Priory also held a manor at Strumpshaw, near Norwich, where there is a broad, but no records of peat production have survived.

In a situation where exhausted sections of a turbary were flooded, and peat was being dug with turf-spades from new sections, might it not be convenient to use boats to transport those turves to the edge of the turbary? Might it not also have been as convenient in the 12th and 13th centuries, as it clearly was in the 14th?

(Note: It has been claimed that medieval wheelbarrows were used for transporting turves on site, even that their wheels left ruts in the peat. There is no evidence at all for either of these assertions. See under "How did they really do it?"/"Conclusive evidence").

If the broads originated as small, adjacent pits, each of which flooded as soon as it was completed, why go to the trouble of joining them together? How would it have been done? These records contain important clues.

- Methods other than conventional digging would always have been necessary to extract the valuable peat from the strips of fen which separated adjacent, flooded pits, before shaping it into turves.

"It is this division into two processes which appears to be responsible for the much greater cost of producing turves . . . ."

Smith leaves a great many questions unanswered. If costs are indeed related principally to the work method used, why, having risen because of the introduction of more expensive techniques, do they not remain constantly higher? Why, instead, do they fluctuate and then fall back again? Why do they differ significantly between one location and another? Why is the cost of 'making turves' at Scratby in 1297-8 the same as 'ferrying turves' in 1342-3? Why did it cost Hemsby 10.8d. per 1000 to 'make' turves 'with ferrying' in 1317-18, but only 8d. per 1000 in 1318-19?

Smith's interpretation is clearly based on the assumption that direct labour is the principal, if not the sole cost element:

a more laborious method is introduced; it takes more man-hours to produce a given number of turves; the cost of the turves goes up.

Apart from providing one example of peat diggers' pay dated 1380, Smith states, " . there is little evidence about wages." There is, however, just enough to demonstrate conclusively that his assumption is ill-founded. Out of a total recorded cost of fourpence

- The direct labour cost of producing 1000 turves at Martham in the 1290's would have been a penny, or, at the most, a penny halfpenny, if wage labour was used.

- If, as is probable (see under "The price of peat"), labour services were used or commuted, the labour cost would have been nil.

This is a subject which requires detailed analysis of all the available evidence, and this I have attempted elsewhere (see under "The price of peat."). My conclusion is that

- the major element in the recorded cost of peat produced at manors held by Norwich Cathedral Priory was not direct labour, but the value of the peat itself.

When turves are dug from a turbary, some of the value of the turbary is contained in them; every time the lord of the manor throws turves onto the fire in his great hall, or sells some turves to somebody else, he disposes of part of his turbary, and the value of his assets diminishes. The true cost of a turf must therefore include the value of the peat which it contains. To any businessman this is basic, common sense. The Priory's manors were big, profitable businesses with professional managers, the bailiffs, who were responsible for the accounts, and who were all trained by the Priory to the same standards (see below). To a bailiff it would also have been common sense that, if the market price of peat goes up or down, the value of peat in a turbary goes up or down accordingly.

- Between 1305 and and 1310 both grain and livestock prices almost doubled, and stayed high until the late 1330's (Briggs, 1999);

- most historians agree that this was price inflation, caused by shortages arising from the dreadful weather (ibid.). (See under "The price of peat".)

When it gets very cold or very wet, demand for fuel increases. If, at the same time, the bad weather creates temporary difficulties with production, shortages will occur. What happened to the price and cost of peat during this same period?

Source: Smith, 1960

Barley prices at Martham follow a similar pattern. In 1314, 1315, 1316 and 1318, the harvests were disastrous, grain prices were sky high and there was famine. In 1319-20, there was a bumper harvest due to the excellent weather, and the price fell to a low 3s. 2d. per quarter (Cornford, 2002). There was a drought in the summer of 1334-5; the harvest was saved, but peat was sold at only 9d. per 1000 (ibid.).

Why, nationally, did commodity prices return to 13th century levels after 1337? Because, after three decades of extreme instability, the weather became more settled, and harvests improved.

- The only truly variable cost element in the production of turves is the value of peat.

- Costs rose, fluctuated and fell back to thirteenth century levels during this period because they were tracking prices.

- The Priory employed a simple, common sense form of basic inflation accounting for this small, but unique part of its profitable manorial businesses.

(Smith formed a different view of peat price movements in this period - see under "The Price of Peat")

The third period

"It may well have been new floods which put an end to the large-scale production of turf at Martham in the 1340's. The turf pits there were deep, and once they had become completely flooded the dredging of turf would have become impossible and little turf remained between the old cuttings and the upland margin."

Under what conceivable circumstances, consistent either with our present knowledge about medieval water levels or with Green's theories, could it possibly have taken a period of around forty years for peat pits first to become 'partially' and then 'completely' flooded?

Apart from the evidence of low grain prices and more stable weather conditions, Smith himself reports, from the nonarum inquisitiones of 1341, "the large-scale exploitation of turf" in north east Suffolk, with annual output totalling c.750,000 turves. While this same source provides some evidence of land loss due to coastal erosion, there is no evidence of floods having affected the value of the peat fens and turbaries.

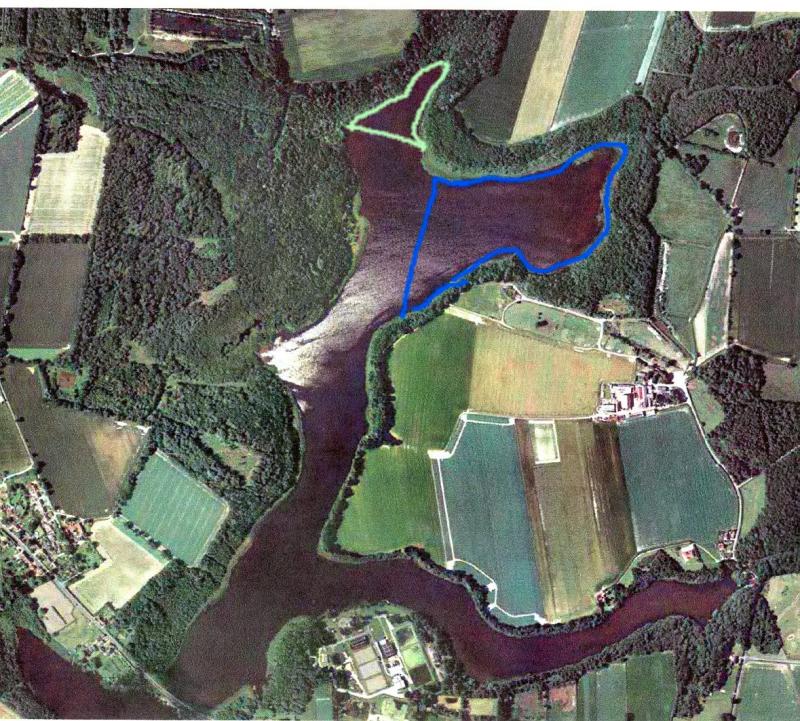

"In parts of the big downstream side valleys, near the thickly populated 'settlement islands' of Lothingland and Flegg (see Part III), most of the peat appears to have been removed in its entirety down to the inferred critical levels controlled by water seepage." Lambert and Jennings, 1960

" . . . and little turf remained between the old cuttings and the upland margin." Smith, 1960

"[Ormesby, Rollesby and Filby Broads] follow their valley contours closely and for the most part have shelving sand or gravel sides". Lambert and Jennings, 1960

The Martham, Hemsby and Scratby turbaries formed part of the basin of Ormesby Broad, at the head of the big downstream side-valley on Flegg.

- All the actual facts point unerringly to the conclusion that all the reserves of peat in these turbaries were exhausted.

SOME MORE FACTS

"At first the two manors [Hemsby and Martham]were let for rent, but the price-rise at the beginning of the thirteenth century meant that fixed rents were a wasting asset. With the increase in the price of grain it made economic sense for the Priory to take the estates in hand and to enjoy the produce and profits. In 1257, when the rent was two years overdue, the Priory ended Sir Walter de Mautby's lease of the two manors. . . . For the next two hundred years a Bailiff appointed by the Priory ran the two Flegg estates which were the most valuable corn manors in the Priory's possession." Cornford, 2002

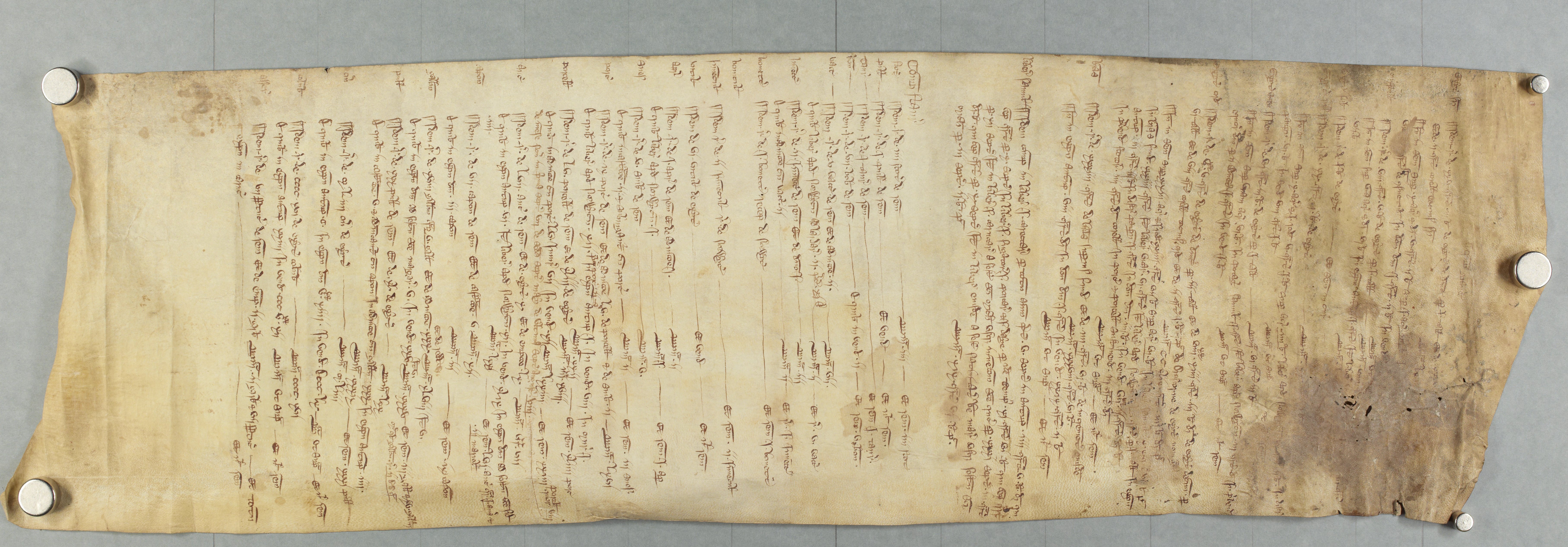

"The earliest account rolls from 1261 to 1274 contain no mention of turf, but from 1294-5, immediately after the detailed rental and survey had been compiled . . . . turf accounts were made more or less systematically". Smith, 1960

Unlike South Walsham Hall, turf production seems to have been a very minor aspect of the affairs of Martham Hall. Not only have no turf records survived before 1294-5, but it seems probable that none were made, and that they were only introduced after a major survey of the manor's assets in 1292. Accounts have survived for twenty two of the years between 1300 and 1350, but only sixteen of these mention the production or sale of peat.

"For at least twenty six years, from 1287 to 1313, Adam de Bawdeswell was the bailiff of both Martham and the larger manor of Hemsby. He must have received some training from the steward of the Monastery, and have had a method of keeping records of income and expenses of the manor. . . . . The actual writing of the accounts was the work of a monastic scribe, who visited the manor to take the account from the bailiff". Cornford, 2002

The foregoing provides an irresistible case for combining the Martham and Hemsby records into a single sample for the purposes of analysis and interpretation, and a powerful one for including the turf accounts from all the Priory's manors (as in the Appendix beneath).

"There were two manors in Martham, the Priory manor and the Gunton manor [or Moregrove Manor]. The Hall, or manor house of the Priory manor, lay to the south of the village at the end of what is now Hall Road. . . .. The Gunton manor house was in Moregrove Field to the north of the village. . . To the south of the Hall lay meadows and marshes . . .. Beyond the meadows were the turbaries or peat diggings which have since become part of Ormesby Broad. The villagers could lease half an acre in the peat diggings for an annual rental of 1d.. . . .. Medwesyk was a low lying area along which a stream ran to the river Thurne. Most of the demesne meadows lay in this strip of land. . .. Seven acres of demesne pasture lay at Breyflete by the river Thurne and three acres of demesne turbary at Medwesyk. On the whole this seems rather a small area of meadow pasture and marsh for a manor the size and importance of Martham."

"The Long family may have specialised in the production and sale of peat. Whereas most tenants rented an acre or half an acre of turbary in the South Fen, the heirs of Nicholas Long held two acres and a meadow."

"A few holdings have duties such as cutting turves or haymaking, which are not found on the standard holdings." ibid.

All of this suggests firstly that the manor's demesne turbary assets were quite small, and played a very minor part in its operations. What is now West Somerton Broad was part of the estates of a different manor, as was Martham Broad. Much of the South Fen turbary was rented out rather than used for the manor's direct benefit, and in consequence ouput went unrecorded. The Cathedral Priory in Norwich imported substantial quantities of turves (up to 400,000 p.a.) from Ormesby and other sources, but Martham and Hemsby were not involved.

Although Smith claims that "substantial manorial revenues were drawn from the sale of both tithe and manorial turves" between 1305-6 and 1339-40, total annual turnover at Martham Hall never exceeded 16s 0d., and was usually much less. The manor's entry into the market was presumably a response to the extremely favourable prices available in this period, but volumes were nothing like those achieved by South Walsham Hall (£9. 12s. 6d. in 1270-71) in the previous century, when prices were only 8d or 9d. per 1000.

The three acre Medwesyk demesne turbary is recorded on the survey of 1292, and continued in use into the 15th century. This was a small part of a large area of fen between Bastwick and Martham, bounded to the north by the river Thurne, and to the east by the road to the ferry. Although it was clearly in existence during the same period as the South Fen turbary, there is no evidence that there was ever a broad there. It is possible that peat digging was always confined to the surface peat, which allowed the peat to reform and the fen to be conserved. (see under "Why did they stop?")

Secondly, the evidence as a whole is, again, highly suggestive of the peat being dug in small, separate sections, rather than from a "great pit".

Thirdly, the existence of only a few tenants with turf cutting labour dues is entirely consistent with relatively small number of subsistence turves being produced each year at no direct labour cost.

A DIFFERENT VIEW OF THE EVIDENCE

- Turves were cut from small pits throughout the life of the demesne turbary in Martham Hall's South Fen.

- In some years, the walls of peat which separated these small pits were hacked and dredged up to be shaped into turves.

- This not only maximised extraction, but also created larger areas of open water, to allow free passage for the small boats which were used to ferry turves and bulk peat to the edge of the turbary.

- Inflated peat prices in the first part of the fourteenth century induced the manor to sell small quantities of turves.

- The inflated value of peat during this same period is correctly reflected in production costs.

- The South Fen demesne turbary was abandoned when reserves of peat had been exhausted.

APPENDIX

back to: "The Historical Evidence in Detail" HOME

Copyright 2009 The Medieval Making of the Norfolk Broads. All rights reserved.

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards