THE ORIGIN OF THE NORFOLK BROADS

A CLASSIC CASE OF CONFIRMATION BIAS

BILL SAUNDERS

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards

The price of peat

The bulk of all the sales and cost data come from the period 1265-1350, when the Norwich Cathedral Priory records are the only source of cost information, and, along with the manor of South Walsham Hall, one of only two sources for sales and purchase statistics. The only surviving data from St.Benet's Abbey come from the second half of the fourteenth century, but there are very little of them, or of anything else from other sources. Fifteenth century records are nearly all from the single source of Bartonbury Hall.

Costs are rarely broken down, although in many cases it is clear that at least two cost elements are included in the total.

With a single exception, costs are for subsistence turves, not turves produced for resale.

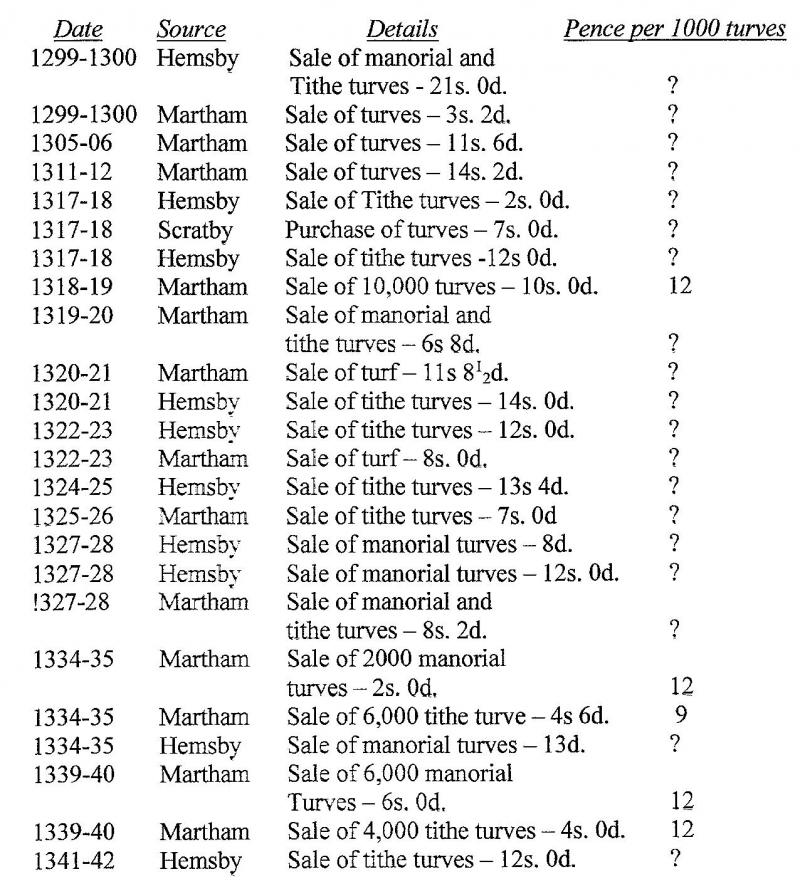

With few exceptions, fourteenth century sales accounts for Norwich Cathedral Priory manors provide the total annual revenue without any unit sales figure to complement it.

- All this makes it difficult, although not impossible, to compare like with like and to reach even tentative conclusions.

Smith (1960) confined himself to the following seemingly confident assertions:

"The total cost of making of making turves shows a sharp increase to 9d./1000 in 1305-6, more than double the costs recorded in earlier years. Costs declined in subsequent years, but never fell to the levels of the thirteenth century."

"It is this division into two processes which appears to be responsible for the greater cost of producing turves after 1305. Costs were so great as to remove the prospect of profits, which had been considerable before 1300, but negligible after 1305, since the prevailing price remained constant at about 1s. 0d, per 1000."

Appendix 1 combines all Smith's data in a single table.

"Costs declined in subsequent years, but never fell to the levels of the thirteenth century."

As already noted in "The Making of Ormesby Broad" (q.v.), this statement is not supported by the facts.

Costs rose as Smith stated, fluctuated and then did fall back to thirteenth century levels.

"It is this division into two processes which appears to be responsible for the greater cost of producing turves after 1305."

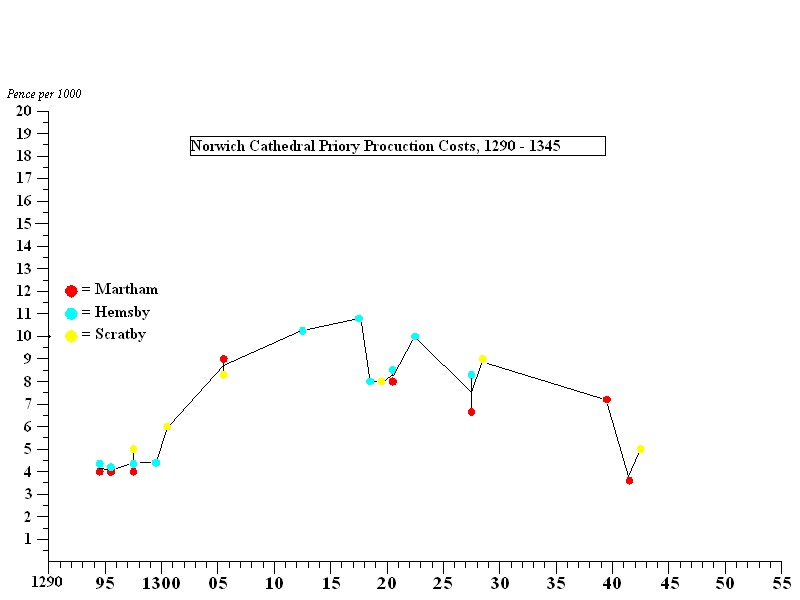

Up to 1301-02, 'making' subsistence turf at Martham cost 4d./1000, at Hemsby 'making' or 'cutting' cost 4.2 to 4.4d./1000, at Scratby 'making' 5.95d./1000 or 'making and carrying' 6d..

In 1305-06, 'Scouring [10,000] turves with carriage of fen' cost 9d./1000 at Martham, 'Scouring [30,000] turves with cutting' 8.3d./1000 at Hemsby. (These are the only two surviving references to turves being 'scoured', although in 1379-80 Martham spent 18d. "In scouring the doles of workers digging peats").

Smith interprets this clearly different description of making turves at Martham as a completely new method, introduced because the basin has started to flood, despite the fact that there is no mention of water or boats. Smith argues that its introduction is responsible for the increase in costs, presumably on the grounds that the method sounds more laborious and time-consuming than conventional cutting, the inference being that it would take more man/hours to produce a given quantity of turves.

This argument is based on the assumption that the major element in the total cost figure is direct labour, that most if not all of the 4d. which it cost Martham to produce 1000 turves in the 1290s, and therefore of the 9d. which it cost in 1305-06, was money paid as wages to the peat diggers. Is this assumption valid?

"A good day's digging in nineteenth century Broadland yielded 1000 turves according to R.F.Carrodus" Smith, 1960

There is no direct contempory evidence for how many turves a medieval turbary worker might have been expected to dig in a day, but common sense dictates that some standard would have applied, and this figure, as seemingly the established tradition in Broadland, was used by Smith in calculations about extraction rates and the period of time it might have taken to create the Broads.

Traditions have to start somewhere, and 1000 turves represents about two turves a minute over a full working day, a sustained rate well within the compass of anybody used to manual labour, even allowing for the turves to be stacked; so it would seem a reasonably conservative basis for rough calculation. (Reputedly, some men were capable of digging twenty turves a minute, but this rate could surely not be sustained for long).

"The digging of turves in 1380 at Hoveton was paid for at the rate of 4d. per day, for Henry Day worked then at the digging of peats for 7 days and was paid 2s. 4d, but there is little evidence about wages." ibid.

On this basis, all of Martham's costs in the 1290s are indeed accounted for by labour, but while there is, certainly, little direct evidence about peat diggers' pay, there is more evidence about wages.

In the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries at Martham:

"A growing population meant a ready supply of cheap labour for such tasks as digging and spreading marl, dung-spreading, breaking up the ground, hoeing and weeding. The usual wage for this work was 1d. or 1 1/2d.a day." Cornford, 2002

"Before the Black Death [at Martham], 8s. 4d paid the wages of all six farm workers on the manor each year, but by 1378 the cost had more than trebled and had risen to £1 11s." ibid.

"[After the Black Death] Craftsmen were also paid more, taking 5d. a day, or 7d. if they had a labourer with them; before the plague their daily wage would have been 2d. or 3d." ibid.

- A wage of 4d. a day in 1380 would have only been 1d. or so in the 1290s, such were the effects of wage inflation.

- Peat digging was just another task for unskilled manual labour.

There is corroboration for this

"An extent of the manor of Burgh in 1328 recorded the liability of customary tenants to 14 days' digging in the turbaries or a payment of 14d. in lieu." Smith, 1960

At a St.Benet's manor on Flegg, not far from Martham, some of the tenants, as part of their 'terms and conditions of employment', were obliged to dig peat in their lord's turbary for fourteen days each year, without receiving any pay. As with all these feudal services and 'labour dues', there was the facility for either party to avoid physical performance of the services by requiring a payment to be made in lieu, that is to 'commute' them. The underlying principle was that if you did not perform the service yourself, you had to pay for somebody else to do it in your place.

- The 'commutation rate' for peat digging labour dues, and therefore presumably the rate at which replacement workers could be hired, was but 1d. a day.

"Similarly labour services, or commuted payments were taken at Martham, South Walsham, and Hoveton and probably elsewhere. Wage labour was also used." ibid.

At Martham, peat digging labour services seem to have been confined to two or three households (Cornford, 2002), but annual production was limited to 5000-6000 turves for subsistence in the 1290s, never more than 21,000 thereafter. The rules over labour service were enforced.

"If a tenant was not required for a day's work he had to pay the price of the service. In the bailiff's words 'the work was sold' to the tenant for the stated sum. The earliest bailiff's accounts from 1265 onwards, show that many services were 'commuted' or transformed into cash payments in this way." (Cornford, 2002)

The Bailiff, Adam de Bawdeswell, "preferred to use paid labour which could be hired as an when necessary for many of the tasks on the manor" (ibid.), the cost being offset by the commutation of labour services.

- If wage labour was used, then labour costs only account for 1d., at the most 1 1/2d, out of the total cost of 4d. for 1000 turves in the 1290's.

- It seems highly probable that labour services or commuted payments were taken, in which case labour costs were nil.

There was, therefore, at least one other element included in the total cost figure, larger than labour, and therefore more likely to be responsible for changes in the total. Smith's interpretation of the evidence is thus open to very considerable doubt, and anyway leaves too many questions unanswered:

- If the increase was caused by the introduction of different, more costly methods, why do costs not remain constantly higher, rather than fluctuating and then falling back.

- Why were like-for-like costs at Hemsby and Scratby usually higher than Martham?

- Why did 'making and ferrying' turves at Hemsby cost 10.8d./1000 in 1317-18, but only 7.6d. in 1318-19?

"Costs were so great as to remove the prospect of profits, which had been considerable before 1300, but negligible after 1305, since the prevailing price remained constant at about 1s. 0d. per 1000"

Hemsby sold turves at 12d./1000 in 1294-95, while subsistence turf cost only 4.4d. to make, so profits were indeed considerable, even to some eyes, perhaps, excessive.

- So why would the joint bailiff decide that Martham, where previously no peat had been sold, should enter the market in 1305-06 in order to join Hemsby in obtaining what Smith describes as 'substantial revenues', at the very point in time when profits became 'negligible'?

- Why would anybody bother to produce any peat for sale if there were no prospect of profit?

- Why were prices not driven up by the increased costs?

Smith offers no explanation. This is doubly puzzling because the price of many other staple commodities started to escalate in just this same period.

"There was marked fall in temperature at the beginning of the century, which produced what has been descibed as a mini ice age, and between 1315 and 1317 there were great floods, compared by contempoaries to the biblical flood. Harvests failed, and there were also sheep and cattle plagues . . . . . ., together these disasters caused what some historians have described as the worst agrarian crisis since the Norman conquest, Scarcity affected the towns as well as the country." "A Social History of England", Briggs, Viking, 1984

"Difficult economic problems were revealed in the first decade of the 14th century, although their extent has been vigorously debated. The initial problem was inflation for in places both grain and livestock prices almost doubled between 1305 and 1310, and went on to reach new heights bewteen 1315 abd 1321 . . . . .. Many prices remained high until 1337, then dropped and stayed low for twenty years." ibid.

This was price inflation caused by the grave shortages which occurred as a result of the bad weather. This national picture is certainly reflected locally in grain prices and other records at Martham (see Appendix 3). There was no form of price control, very much the reverse.

"In the year after a poor harvest, the price of barley rose sharply, and this must have caused hardship for many peasants living near subsistance level. The manors always managed to sell a good deal of barley in years of bad harvests, even in the Great Famine [1314-1316]. With higher prices they often had a better cash return, even if they sold less grain." ibid.

It was the Priory itself that provided any alms for the poor, not its manors.

The very cold weather would have increased the demand for peat, and very wet weather could well have had a temporarily adverse effect on production, as well as increasing demand. Was peat really treated differently to the manor's other products?

In view of the dearth of unit sales figures and the economic background, it seems almost perverse to interpret this information as demonstrating a constant price of 12d./1000. Any sum of money expressed in whole shillings is inevitably divisible by twelve. While an annual revenue of 12s. 0d. might seem suggestive of 12,000 turves being sold at 12d./per 1000, it is equally suggestive of 9,000 at 16d., 8,000 at 18d., 6,000 at 24d. or 24,000 at 6d. (see Appendix 2 for all the possible options).

Clear cost and sales information coincide in only two years: in 1305-06 subsistence turf cost Martham 9d. per 1000 to produce, and turves were sold at 12d..; in 1318-19 Hemsby's costs, which were usually higher than Martham's, were 7.6d., and both manors sold at 12d.. However, since the 'financial year' started at Michaelmas, the cost of turves produced, say, in July, 1294 would be recorded in the accounts for 1293-94; if these same turves were not sold until October, 1294, the sale would appear in accounts for 1294-95.

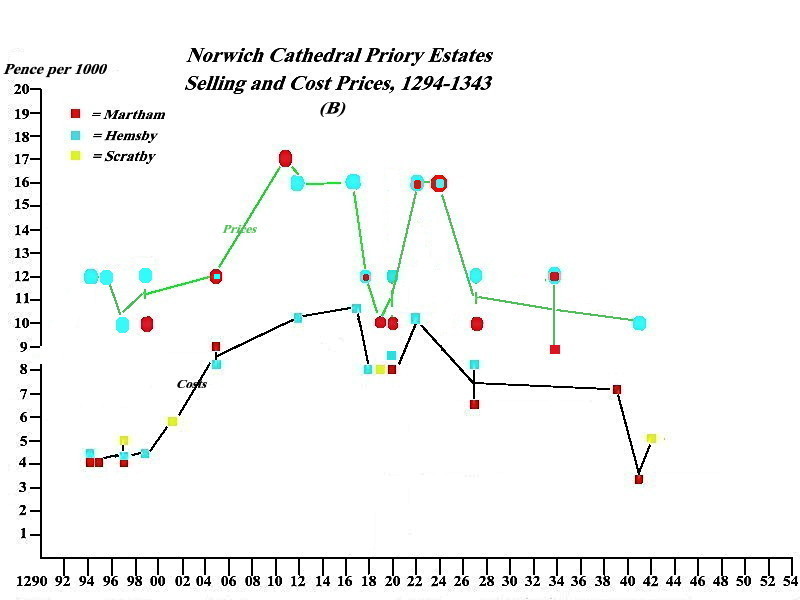

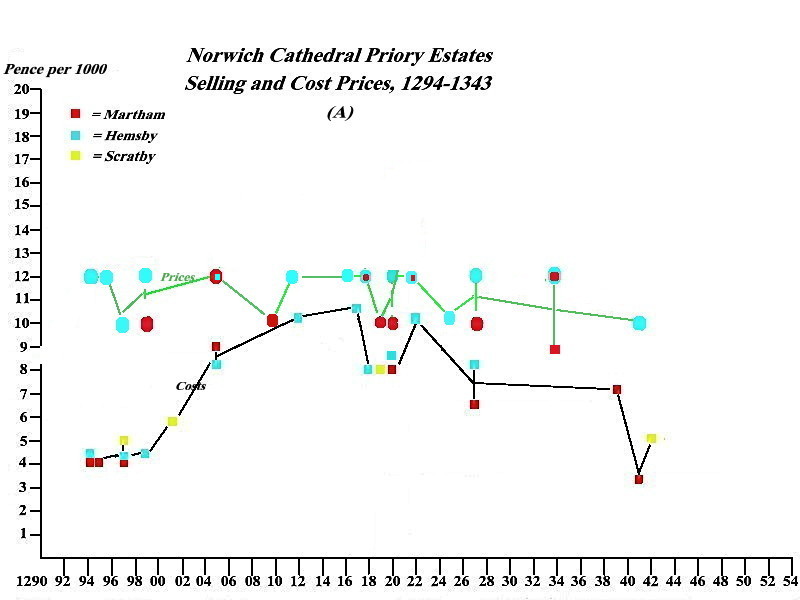

On the basis of exactly the same facts, and with equal mathematical legitimacy, you can have prices remaining at around 12d. per 1000 with a negligible or non-existent gross margin in some years . . . .

. . . or you can have prices and costs tracking each other with an acceptable margin in each year (save possibly 1305-06 and 1320-21).

This movement in peat prices conforms closely to the movement of barley prices at Martham which reveal bad weather in 1294-5, disasters between 1313-14 and 1315-16 and again in 1317-18, but a bumper harvest in 1319-20, with the worst being over as early as 1326-27. (See Appendix 3) The correlation is close, although not exact; but then grain was sold quarterly as peat may also have been, with significant price variations in the same year; the peat digging season and the harvest, which usually started on August 1st at Martham, were at different times in the year.

- This second scenario is consistent with the recorded data, with economic trends locally and nationally, with contemporary local practice, and with common sense; as compared with Smith's thesis, it would therefore seem by far the more probable option.

In 1379-80 Martham costed 9000 turves "made for money" at 9.4d. per 1000. In 1383 St Benet's Abbey produced 100,000 turves at 3.4d. per 1000, and another 100,000 at 3.2d.

The 'ferrying' of enough bulk peat to make 1000 turves cost Martham 5d. in 1323, and 4.8d in 1340; at Hemsby in 1323, the cost was 5.6d. In 1438, when wage rates were about four times higher, exactly the same quantity of bulk peat cost only 6d. at Bartonbury Hall.

- The costs at St.Benet's Abbey and Bartonbury Hall are both in line with wage rates for their period, and thus consistent with containing only the one cost element, direct labour.

- The size of the discrepancies between Norwich Cathedral Priory's costs and those from these other sources is explicable by different accounting principles, with the latter's costs including another element.

The owner of a turbary worth, say, £10, pays some men 5s. 0d. to dig up a quantity of turves amounting to one tenth of the peat in his turbary. How much should he charge for these turves, simply to break even on the transaction?

If he only charges 5s. 0d. to recover his direct labour costs, he loses £1; after ten years the turbary would be exhausted, and he would be £10 the poorer.

His break-even cost is £1 5s. 0d., to which he is entitled in medieval times to add a fair and just amount by way of profit.

To add an excessive amount for profit and take unfair advantage of others would be a sin in the eyes of his church akin to usuary.

If he uses these turves to keep his own home fires burning, his £1 5s. 0d. literally goes up in smoke.

The amount of evidence is very limited, but what there is suggests that Norwich Cathedral Priory's accounting for the costs of peat production was based on simple, common sense principles, at least from the time of their earliest record in 1373; it very properly included the value of the peat itself as a major element in the total cost figure.

The higher level of costs at Hemsby and Scratby are attributable to one of two factors or a combination of the two

Hemsby and Scratby had a higher proportion of 'free' tenants than Martham.

Both were further from their area of turbary and would have incurred higher transport costs than Martham.

Unfortunately there is no source of cost data other than the Priory to provide any comparison until the second half of the fourteenth century, when, as noted above, there is a clear discrepancy between the Priory and St. Benet's Abbey. It is perhaps worth noting here that the latter, in addition to holding manors with turbaries, also, and unlike the former, appears to have leased and operated a large number of turbaries directly - turbaries which thus were not part of the business of a manorial estate..

"For the next two hundred years a Bailiff appointed by the Priory ran the two Flegg estates which were the most valuable corn manors in the Priory's possession." Cornford, 2002

As already noted under "The Making of Ormesby Broad", peat production and sale was a very minor aspect of operations at Martham in particular, but also at Hemsby. At Martham "half the barley crop was malted on the farm and most of that was sent to the Priory" (ibid.), most of the other half was sold locally for between £6 and £27 p.a., usually about £16; from barley sales alone, "The neighbouring manor of Hemsby contributed £50 in 1294-95 and £69 in 1295-96, but more often about £20." (ibid)

- Sales of manorial turves never produced more than about 15s. in any year, often less. (c.f. South Walsham's final year of peat sales: 52,000@ 8d./1000 = £1 14s. 8d., having declined from 255,300@9d./1000 = £9 11s. 6d. in 1270-71)

Up to 1300, peat cost accounts are terse, but sales accounts usually contain an annual figure for total unit sales as well as total revenue; the profit available to Hemsby looks very generous indeed.

After Martham has entered the market, from 1305 to 1329,

costs rise, dip and then rise again,

additional detail is provided: 'ferrying' or 'carriage' are identified as elements included in the total cost; different, and presumably more labour intensive methods are mentioned in the years when they used.

At the same time, the sales accounts stop providing unit sales figures, except for the three years

- 1318-19, when the price was 12d./1000, and we know the weather was fine,

- 1334-35, when prices were 12d./1000 and 9d./1000, and we know there was a drought.

- 1339-40, when the price was 12d./1000. No harvest records have survived for this year, but grain prices were normal in 1338-39 and 1340-41.

All this may be coincidental, but it is consistent with and perhaps even suggestive of, a certain obfuscation during a period when profits might have appeared excessive. No grain prices were recorded at Martham in the two years of the great famine 1314-15 and 13-15-16.

Additional cost elements like transport are basically non-variable, and could not account for the scale of the initial increase in total costs in the early fourteenth century, nor for the subsequent marked fluctuations.

- If the market price of peat goes up or down, then so too does the value of the peat in a turbary.

- This is the only truly variable cost element.

The only rational conclusion, albeit a tentative one in view of the dearth of evidence, is that Norwich Cathedral Priory developed its simple, common-sense accounting principles to accommodate the persistent economic problems of the early fourteenth century by adopting a simple form of basic inflation accounting.

- It is not increasing costs which force up peat prices, but vice versa.

Back to: "The Historical Evidence in Detail" HOME

Copyright 2009 The Medieval Making of the Norfolk Broads. All rights reserved.

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards