THE ORIGIN OF THE NORFOLK BROADS

A CLASSIC CASE OF CONFIRMATION BIAS

BILL SAUNDERS

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards

How did they really do it?

"How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?"

"The Sign of Four", Conan Doyle

"To what extent is the theory of the artificial origin of the broads dependent on the mean water-table being significantly lower than it is today, or put more simply, could peat have been dug to the observed depth if water levels had been only, say, about a metre lower than they are today?" George, 1992

Martin George appears to be re-fighting battles long ago won and lost; the artificial origin of the broads was no longer under dispute; the answer to his question was already plain: the theory is not at all dependent on a significantly lower water table, since peat was dug from the observed depth, and "the relationship between the mean water-table in the rivers and the level of the adjoining fens has varied little over the centuries" (ibid.).

There are two more pertinent, closely related but separate questions which have to be answered:

The first, which is addressed by Martin George, is: "How did the inhabitants of medieval Broadland dig up such large quantities of peat from depths well below the water-table in the fens?"

The second, which then needs to be addressed, is: "Why did this result in the huge flooded pits which are the Norfolk Broads?"

It has been clear since the 1980s that, to create the broads, peat was dug up with turf-spades not just from below the mean water-table, but from below the level of low tide in the rivers and nearby sea. It would have been impossible to use a turf-spade under water, so how did they keep such deep pits dry while they were digging up the turves?

- It would have been impossible to keep water out of the pits.

- It would have been impossible to use the force of gravity to drain the pits, even with an elaborate system of tidal sluices.

For Joyce Lambert's "basins the sheer size and depth" of the broads, logic dictated the use of a device or system to lift and eject large quantities of water; Martin George's additional logic dictated that no device would have been up to the task unless "the diggings were fairly small, and were kept isolated from their neighbours by baulks".

"In the summer of 1953 I dug a bathing pool at Long Gores in Hickling, Norfolk, which with its large island covers a good three quarters of an acre. I fell naturally into the medieval method - the obvious one - for extracting peat below the water-level, by digging pits, and isolating them from each other, leaving bars between to be cut later when re-uniting the waters." "The impermeability of peat and the origins of the broads", Marietta Pallis, Glasgow, 1956

"When I began digging the pool, I had taken for granted that peat was permeable, now I do not think so. The impermeability of peat is quite sufficient for the extraction of pressure peat to a depth of eight or ten feet, and more, provided there are adequate bars; three feet should be ample." (ibid.)

(Marietta Pallis provides more information about this remarkable lady and her pool.)

So slowly does water seep through peat which is compressed by the weight of the ground above that Marietta Pallis found it possible for her workforce of four men to dig up peat from as deep as ten feet or more (she needed only seven feet for swimming), and to extend the pit until too much water had accumulated; when that happened, they started a new pit, leaving a 'bar' at least two feet wide to dam it off from the earlier pit.

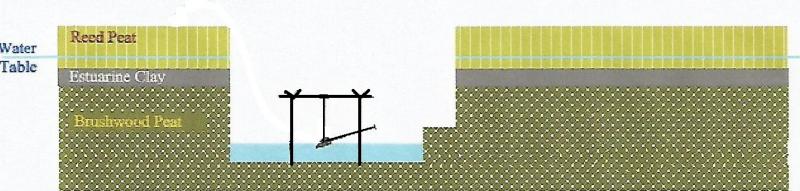

That is not to say that no bailing at all was needed. Pallis records a sharp ingress of water when the initial digging penetrated the level where the decaying roots of the surface reed peat rested on a layer of estuarine clay or 'ooze'. This was only temporary, and once the digging got down to the layer of brushwood or 'wood' peat, seepage was much reduced and the requirement for bailing 'at a minimum'.

All the bailing was done with simple, light-weight, hand-held scoops and buckets, capable of ejecting water rapidly in relatively small amounts from the small, shallow, initial diggings, and also of accelerating it up and out of such deep pits, albeit with the aid of a step-up cut into the wall (see below).

Martin George cited three examples in his 1992 book of Marietta Pallis's work as a botanist and ecologist, but not in his chapter (4) devoted to the origin of the broads. He knew of the pool, since Lambert provided a description of it in 1960 (see below) but he did not cite either of Pallis's own articles about it as a source, so, like most authorities, he was presumably unaware of her exact method and of her observations.

Pallis and George thus seem to have arrived independently at the same inescapable conclusion, albeit at different times and by different routes:

The broads cannot have originated as "great peat pits", but as much smaller, adjacent pits, separated one from another by bars or baulks.

- This is the only way peat could have been dug up by hand from such depths under the conditions which prevailed. It would have been impossible to keep big pits dry, even with the aid of a viable bailing device or pump.

On the question of "How did they dig up peat from such depths?", the choice thus ceases to be the simple one, originally proposed by Joyce Lambert, between very low water levels keeping great big pits dry while the peat was dug up, or an 'engineering' solution involving pumps or bailing devices.

It is now a simple choice between two similar engineering solutions.

- Either: small pits which are kept dry with hand-held implements while the peat is dug up; once a pit floods, or is allowed to flood, it is abandoned, and when more peat is required it is dug from a new, adjacent pit.

- Or: fairly small pits which are kept dry with a 'device' while the peat is dug up; each pit is then allowed to flood temporarily, before being bailed out again for more peat to be extracted, subject to a 'fairly small' limit to the overall area; a pit which has reached this limit is abandoned and becomes permanently flooded; more peat is then dug from a new, adjacent pit.

A rough specification of the bailing equipment needed for each option would be:

Hand-held implement(s) - simple, cheap construction allows one per available worker - capable, within limits, of keeping a deep pit free of water while the pit is being dug - impracticable for bailing out a deep pit of any size once it has become flooded.

A higher capacity bailing device or system - more substantial, more expensive construction - one man operation - capable, within limits, of keeping a deep pit free of water while the peat is being dug - also capable of bailing out a flooded, deep pit so that more peat can be dug from it, and the area of the pit extended, up to a 'fairly small' practical limit.

There is direct evidence that the former method worked under the conditions which prevailed in an area of grazing marsh near Hickling in 1953; although the resulting basin is still not very big, the technique provides for limitless expansion over a period of time, as does the latter method, which, although untested, in principle seems to justify Martin George's (1992) claim:

". . . there seems no reason why [peat] could not have been dug to a depth of 3 m or more, even if the water-table was quite near the surface."

Given the equipment as specified above, either method would have worked at any time when water-levels relative to the fen surface were no higher than they are now, that is from, say, the 8th or 9th century, right through to the present day, unless the fen surface was temporarily flooded.

How likely is it that the equipment specified would have been available?

There can be no doubt that buckets and simple hand-held implements for bailing water out of boats would have existed in medieval Broadland, and these might well have sufficed. There is also a traditional marshman's implement called a 'scoop' or 'slubbing spade':

"This is fashioned all in one piece out of a section of willow trunk; it is about the size of an average garden spade and has a cot-handle (T-shaped); it is shod with sheet iron or steel from and old scythe blade, rivetted on, and a leather hood is attached across the top. This implement is used for throwing water and mud out of dammed sections of dykes.The 'slub' is thrown straight out with the same thrust with which it is collected in the scoop; the leather hood prevents most of the mud and water from shooting backwards off the scoop."; Ellis, 1965

There is documentary evidence that dydles existed in medieval times, so medieval versions of other traditional tools are not unlikely.

In the alternative, apart from this not entirely convincing offering from Brian Moss,

"The compartments were separated by banks of uncut peat and easily [sic] baled by hand or by scoops swung on poles to lift the water over the banks and into the rivers or nearby stream." "The Broads - a people's wetland.", HarperCollins, 2001

the sole candidate for a bailing device or system is the ladle-and-gantry, proposed by Joyce Lambert, seconded by Joseph Jennings, and again by Martin George.

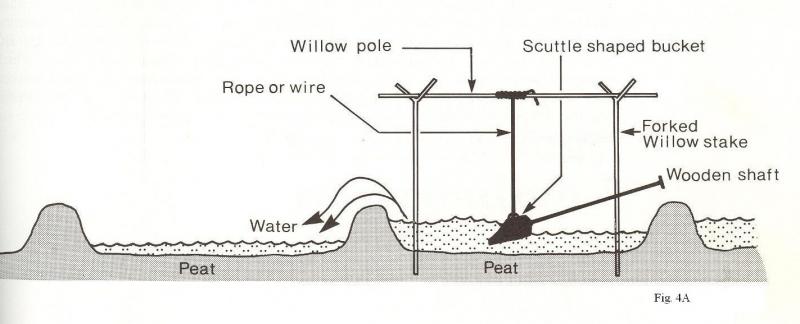

"The 'ladle and gantry' method of removing water from a flooded peat pit, as formerly employed in the Somerset Levels. Anecdotal reports indicate that in the hands of an experienced operator, the bucket could be swung to and fro about 20 times a minute, thus removing about 2400 gallons an hour, as the water in the pit fell, the rope suspending the bucket could be lengthened."

Source: Williams (in litt.) George, 1992

The operator, presumably wearing some form of insulated waders, stands in the flooded pit.

The operator grasps the handle, and propels and guides the ladle to and fro, while its weight, along with that of the two gallons of water which it collects (approximately twenty pounds), is supported on the bottom of the pit via the rope and gantry.

The experienced operator would have learned the best speed at which to swing the ladle, and the best angle of attack for the ladle to strike the water. Too slow and there would be insufficient impetus to expel the water from the pit; too fast or too steep an angle and the ladle would stall on impact with the water; too shallow an angle and little water would be collected.

The ladle can be lowered to gather water from near the bottom of the pit.

Using the rope to raise the ladle above a certain height would have the effect of constricting arm movement, and make it impossible to swing the ladle to and fro. Little more than three feet of water would seem to to be the maximum operating depth.

The relatively slow, pendulum-like motion would enable the operator, with minimum effort over an extended period, to propel the two gallon/twenty pound charge of water over a low barrier at the rate described, as in Martin George's illustration.

This same motion would obviously make it impossible to collect, accelerate and eject the charge of water out of a pit with sides more than, at the very most, about four feet high.

- If the ladle and gantry were to have been translated machina ex deo from the shallow, nineteenth century peat diggings of the Somerset Levels, for which it was designed and built, into the deep Broadland peat diggings of the twelfth century, it would have proved useless.

Something else then? Apart from a bucket on the end of a rope, there is no evidence that anybody has ever devised a manually operated bailing device or system capable of raising water more than about six feet, not Archimedes' Screw, not the shadoof, and certainly not the ladle-and- gantry. If they had invented any kind of worthwhile pump in medieval Broadland, then surely it would have been used at sea; excepting ancient designs lost in the dark ages, the earliest forms of marine bilge pump date from the sixteenth century.

- It would have been impossible to use a turf-spade under water

- It would have been impossible to stop water getting into the pits.

- Drainage by gravity would have been impossible.

- It would have been impossible to keep big pits dry, even with a viable form of bailing system or pump.

- Pumps or mechanical bailing devices are themselves an impossibility in the context of medieval pits as deep as the broads.

Having eliminated the impossible, what then remains? How did they dig peat from such depths when water levels (and the surface of the fen) were no more than a metre or so lower than they are today?

- They used the "medieval method - the obvious one - for extracting peat from below the water level, by digging pits, and isolating them from each other, leaving bars between to be cut later when re-uniting the waters".

"The possibility of the deep digging of peat in the Norfolk fenland even today is often underestimated. Provided the area is isolated from tidal flooding, practical experience has shown that considerable depths can be attained comparatively easily in places where the general water table is only a little below the fenland surface. For instance, an ornamental swimming pool has recently been excavated in the Hickling marshes to a depth of nearly 3 metres entirely by intermittent hand labour without the use of elaborate pumps with the men working well below the level of the water in nearby dykes; and it is estimated that even greater depths could have been reached without difficulty (M.Pallis, 1956; also in litt.). Similarly it is reported that little trouble with inflow directly through the peat was encountered when the Lound reservoirs were dug out upstream of Fritton Lake; most of the water accumulating in the excavations came from a small stream entering at the western end and from springs on the uncovered valley sides (K.B.Clarke, in litt., 1956). And furthermore, a recent excavation of a new length of drain for the Brograve pump, dug to a depth of about 3 metres through the peat is stated to have remained perfectly dry for several days even though there was a full dyke only a short distance away (K.E.Cotton in litteris, 1960). Lambert, 1960

Lambert and Jennings saw the impermeable nature of peat simply as a helpful factor in their speculations about keeping great big pits free of water; it would have made the perennial task of regular bailing easier. Their evidence, quoted above in full, is all anecdotal, but the inference, particularly from the new length of drain, is clear:

- if a deep pit will stay dry for several days without any bailing, then it could be kept dry, with a minimal amount of daily bailing by hand-held implements, for a much longer period.

- Why waste time bailing out a flooded pit in order to enlarge it, when all you have to do is start a new one?

Lambert found a clear correlation between the depth of a broad and its location;

"The remarkably constant level of the floors of the majority of the basins at between 3 and 4 metres from the present fenland surface is sufficient in itself to suggest that beyond this depth conditions generally became too difficult for further excavation, even though good peat deposits could still be found below; and it is significant in this respect that the deepest broads are found in the big downstream side-valleys well away from the river[s] and separated from them by a great stretch of clay, while Dilham, Sutton and Calthorpe Broads, occurring well upstream beyond the limit of the clay are relatively shallow." Lambert and Jennings, 1960

Lambert hypothesised, without direct evidence, that below a certain depth the peat suddenly becomes permeable, and that it is this "critical level controlled by water seepage", determined by the location of the broad, which limited the depth of the digging.

Pallis's empirical approach led her to a different explanation:

"One reason may be the height of the throw-up, whether by spade or bucket scoop up, and I had in some cases to cut a shelf and place a man so as to throw far enough not to soak the edge of the hole and let the water in again. This slows down matters, and may mean extra men.

Another possible reason is that at low levels when one approaches the hards [i.e. the valley floor], the botttom is unconsolidated, fluid almost, and the men sink in and only a bucket can be used. If the hards are taken at about 15 feet and the dug depth is about 10 feet, the weight of the men brings the bottom up, which leaves only about 3 feet to the hards, where at the junction of the peat and the hards, the water, I think, finally comes in. Dr. Lambert, however, gives sections where the hards are 9 metres and over, yet the basins of the Broads remain at the critical depth of 3-4 metres, which seems to dispose of the above possibility, leaving the height of the throw-up as the critical factor." "The status of the fen and the origin of the Broads", Pallis, Glasgow, 1961

Lambert's concept is difficult to reconcile with the impermeable nature of 'pressure' peat, and with Pallis's belief that significant leakage only took place at the junction of the peat and the valley floor. On the other hand, Pallis fails to explain why some basins are deeper, at five metres or more, than her perceived critical "height of the throw-up", and also why some are shallower. The Long Gores pool, which seems to be within the limit of the estuarine clay, is not only much deeper than the nearby Calthorpe Broad, which is outside the limit, but also deeper than most of Hickling Broad.

Pallis's account does, however, confirm other anecdotal evidence that the consistency of the peat itself changes below a certain depth, while still retaining its impermeable character; the depth is variable depending on location, and not necessarily close to the valley floor (Maxted, in litt.). Obviously such a change makes it difficult to stand on the bottom of the pit, but peat of of this 'unconsolidated, fluid almost' consistency would not retain the form of a turf, if dug up with a turf-spade, and would be impossible to handle.

So Lambert and Pallis can be combined to produce a third, perhaps rather more convincing explanation of the factor which limited the depth of the digging, and for the great variation in depth between some broads and others: the consistency of the peat.

To have dug up large quantites of peat from such depths, the inhabitants of medieval Broadland must have created small adjacent pits, isolated by bars or baulks, each of which would have been abandoned to become permanently flooded as soon as it was finished.

However, these are small, flooded pits and not great big, flooded pits. This brings us to the second question posed above: "Why was the result the huge flooded pits which are the Norfolk Broads?"

- The isolating bars or baulks must have been removed.

APPENDIX

The Depth of the Broads.

Joyce Lambert put "the floors of the majority of the basins at between 3 and 4 metres [ten to thirteen feet] below the present fenland surface", but, when the broads were created, they were not as deep as that, because the surface of the fen was lower by about three feet/a metre.

However, for deep digging the critical measurement is the depth below the water table, and that makes things slightly more complicated. For scientific purposes Joyce Lambert's measurements of the depth of the basins were, very properly, shown in metres below 'OD Newlyn', the mean sea level at Newlyn in Cornwall, which is used as a reference point for maps and other accurate, scientific measurements of height and depth. The floors of the majority of the basins are eight to eleven and a half feet (2.5 to 3.5 m) below OD Newlyn.

However, mean sea level at the East Norfolk coast, and mean water levels in the Broadland rivers and fens are historically about two feet/0.75 m higher than OD Newlyn.

In medieval times, the level of the sea relative to the coast, water levels in the rivers, and the water table in the upper-valley peat fens, were all about three and a half feet/a metre (or slightly more) lower than today.

The additional six inches or so between the surface of the fen and the water table would have made conditions better than, but not radically different from today. Any pit dug to a level below the water table would still have flooded.

Since it is the level of the water-table which is critical to deep digging, all of this taken together means that

- when the peat pits were created, the majority were dug to a depth of seven to ten feet below the level of the water table as it was in medieval times.

- The deepest pits were twelve to fourteen feet, the shallowest only three to four feet below the water table.

That is, of course, assuming that the relationship between the mean sea level at Yarmouth and OD Newlyn was the same in medieval times as it is today!!

Copyright 2009 The Medieval Making of the Norfolk Broads. All rights reserved.

The Origin of the Norfolk Broads - a classic case of Confirmation Bias

mallards